According to polls Jeremy Corbyn has emerged as the likely next leader of the British Labour party. If you look at the stances Corbyn takes and took over the past decades, he is quite obviously what you would traditionally call a centre-left politician. Normatively speaking his views don’t come off as being „radical left“, despite him being regularly called so. The views are consistent with core values of social democratic parties all over Europe, even though admittedly most of them seem to have forgotten what is written in their manifestos.

In a keynote speech setting out his economic policy, Corbyn said austerity was a “political choice not an economic necessity”. He said he wanted to see quantitive easing – a form of printing money to create bonds to fund infrastructure projects. He also called or a return to progressive taxation and a clampdown on business tax evasion.

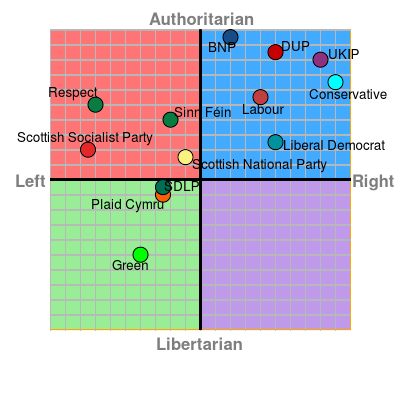

Those and other views can only be considered „radical left“, if you look at them from a position pretty far to the right (which admittedly is where mainstream politics are nowadays). Otherwise they are just regular „democratic left“ positions. It is bloody interesting to watch the reaction of the Labour party’s establishment to Corbyn gaining ground. The leadership seems to fiercely oppose him. Besides the excruciatingly baring „We’d lose big donors„, one of the main flaws Tony Blair and others are trying to pound into the minds of their members is: „People would never vote for Corbyn“. This lack of substance is necessary because the party keeps up the image of being „modern left“ even though objectively it must be categorized as a centre-right party.

Now even if we leave this charade aside, there are still several problems with this argument. One is that it clearly is not the whole point of having a political party to win elections (though it is an important one, because without power you can’t change anything). But at least at some point the representation of the political views of the party members should become a topic, shouldn’t it? Of course you have to keep in mind Labour is not a homogenous group. Its wings are obviously stretched quite far apart and considerable parts of it want it to be exactly how it is. And all this is not to say, Jeremy Corbyn would be the only true representative of Labour’s members, but Tony Blair, Gordon Brown or Ed Miliband were no different. If you win the majority, you are the face of the party – it is that simple.

But even aside from those considerations, about what a party should be, there is something else inherently wrong with the „Voters are not gonna buy it“-argument: It might just be wrong and you won’t know until you try.

Labour’s long dominating right wing acts as if it is on top of the world, when in fact it isn’t exactly getting anywhere close to winning either. In fact, if you look at the results of elections in the last 45 years, three of the four worst results came in the last three elections under Tony Blair himself and his heirs (with the fourth being in 1983, when the party effectively split before the elections). The shift to the right (which Blair calls „modernization“) served the party well in the 90ies but since has apparently lost its attraction to voters (and cost the UK the option to elect a leftist party in the process).

It seems, after decades of pragmatism that steadily and gradually shifted the party to the right, some parts of it are fed up of what is mainly fear guiding their political decision. The fear of getting an even more rightist Tory in Downing Street, if they don’t peg their noses and vote for the lesser evil that is a Labour party with centre-right leadership. They now want their organisation to represent their views again. And if that doesn’t get you the majority (which it still might do), well, so be it!

By re-establishing Labour as a viable leftist option on the ballot and losing the elections, their members might even get the same results from their goverment, even if it has a different colour. Because let’s examine where that Labour-shift would leave the UK. Political debates are now almost exclusively fought on a playground in the right political spectrum. The debates are now for example about favoring cuts vs. favoring fewer cuts while expanding social welfare isn’t really on the table. With a leftist Labour, debates would regain some of those arguments, thus reframing the public deliberation process farther to the left. It is among other things the constant exposure to a certain set of ideas that shapes public opinion. So society seems likely to respond with at least some kind of shift to the left. And even more likely that is what it would do to the Tories, as politcal strategists would suggest to grab more votes from the centre-right, where Labour of course would lose some.

If Labour does not reconvene with its left wing, it doesn’t mean the left is doomed forever in Britain. But the party itself might just painfully slowly vanish into irrelevance as others take its place. Because there is another argument why, instead of shifting to the left, it is rather continuing on the current path that might never win an election for Labour again. It has to do with credibility. Lots of voters have already turned their backs and cast their votes for more leftist parties like the Scottish Nationalist Party, the Plaid Cymru in Wales or the Green party. The Greens gathered almost 20 times as many votes (about 4% of the total turnout) in 2015 as when Tony Blair bagged a landslide victory for Labour in 1997 (0,3%), reaching double digits in some parts of the country. Despite being at a significant disadvantage posed by the UK’s electoral system, they are now comfortably attracting more than a million voters all over the UK. This growth is of course not only fed by disappointed Labour-voters, but to an even bigger extent by disappointment of voters with the Liberal Democrats after their party drowned in a coalition with the Conservatives. But their success slowly establishes the Greens as a more serious force on the political landscape (they bagged 7,5% in the European elections in 2014) and it could help them to attract more of the leftist Labour votes in the future.

Those voter transition processes are very hard to reverse. Labour is at a serious risk of losing those votes forever, if they continue to lose any credibility as a leftist ballot option. That seems to be the most certain way into not ever winning an election again. Because you cannot endlessly shift to the right to attract new votes from there. Eventually you will run out of space, as at some point people are just going to vote for a genuine conservative or wholeheartedly neoliberal party. And others will lose interest in voting for the lesser evil, if that doesn’t even result in successful elections. A lesser evil needs success as a likely option, otherwise it has nothing to offer.

Now seems to be the time for Labour’s rightists to chose their lesser evil. They expected the left wing to follow Blair to where it is now. Not out of conviction but out of pragmatism. The leftists mostly did, up to a point where it became too painful. Now they are asking the rightists to reconcile by supporting a shift to the left. Some of those are now threating to split up the party (as others already did in the early 80ies) and of course they are perfectly entitled to do so. But they should keep in mind that so are the leftists. Which they might think about, especially if they are pretty much openly threatened by a panicking party establishment as soon as one of their candidates dares to pretend to the throne.